For over the last two years of running this project, we’ve met many kind souls who warmly welcomed us to their homes when we were on the lookout for crafts. They are artisans who take pride in their craftwork and who are owners of intangible systems of knowledge that inform craft production.

Through crafts, we’ve learned of their remarkable resourcefulness when it comes to extracting materials from the forest without exhausting them, and that even the most ordinary plants have extraordinary uses—from fibres to food to its medicinal values.

It proved that we have so much to learn from our Orang Asli, if only we took the time to sit, listen, and understand.

Orang Asli make crafts for various reasons, which are discussed further in our previous article. Local initiatives such as Gerai OA, Kraf X, and Manao Craft are keeping Orang Asli craft production alive by travelling to the villages, collecting crafts, and then helping to sell at pop-up stalls, bazaars, and/or dedicated stores.

There are also Orang Asli micro-entrepreneurs who run their own handicraft business such as Asli Makintan Enterprise by Hanim Apeng and Rizmon Enterprise to name a few.

While doing our fieldwork, we also support Orang Asli craft production by following the footsteps of Gerai OA and Kraf X. It’s a perfect arrangement as we’re already heading into the villages (that aren’t already covered by them) and it doesn’t hurt to kill two birds with one stone: collecting stories and crafts. And after two years of dipping our toes in the water, we’ve come across many questions from the public – during our exhibitions and events, as well as through our online spaces – regarding Orang Asli crafts. Here are the two most common questions…

QUESTION 1: WHY SO EXPENSIVE?

Actually, it’s not la.

A basket could range between RM10 to RM50 depending on its size, fineness of the strips, complexity of technique, and the type of fibre used (whether mengkuang, rotan, bertam, bamboo, or others).

A pouch ranges between RM10 to RM40, also depending on the same factors above. For example, Pos Piah weavers put prices based on the size of their crafts.

Handbags could range between RM15 to RM80 depending on its size, fineness of the strips, and the complexity of technique and kelarai patterns. The weaving pattern is generally known as kelarai. It comes in various motifs such as kelarai beras patah, kelarai mata berkait, kelarai tampok pinang, kelarai buntut siput, kelarai anyaman gila and more.

Backbaskets are between RM60 to RM100, which is determined by its size, fineness of the strips, and the complexity of technique and kelarai patterns. For example, Pos Lenjang weavers price their crafts based on the size and complexity of the patterns. Moreover, they are made from either a single fibre or a mix of fibres such as rotan, bertam, sepal, bamboo, and the likes—which are more difficult to harvest than mengkuang.

A mengkuang tikar could be priced between RM40 to RM150, but a tikar made from rotan, bertam or any of the above-mentioned could go up to RM250, all of which depend on the size, fineness of the strips, and the complexity of the kelarai patterns. Above are two examples of tikar from Pos Lenjang weavers.

Note that these are ballpark figures used as examples based on our experience. But if you’re still not convinced, let us break it down further for you.

Crafts are often seen as an end product, rarely the love and labour involved in their making.

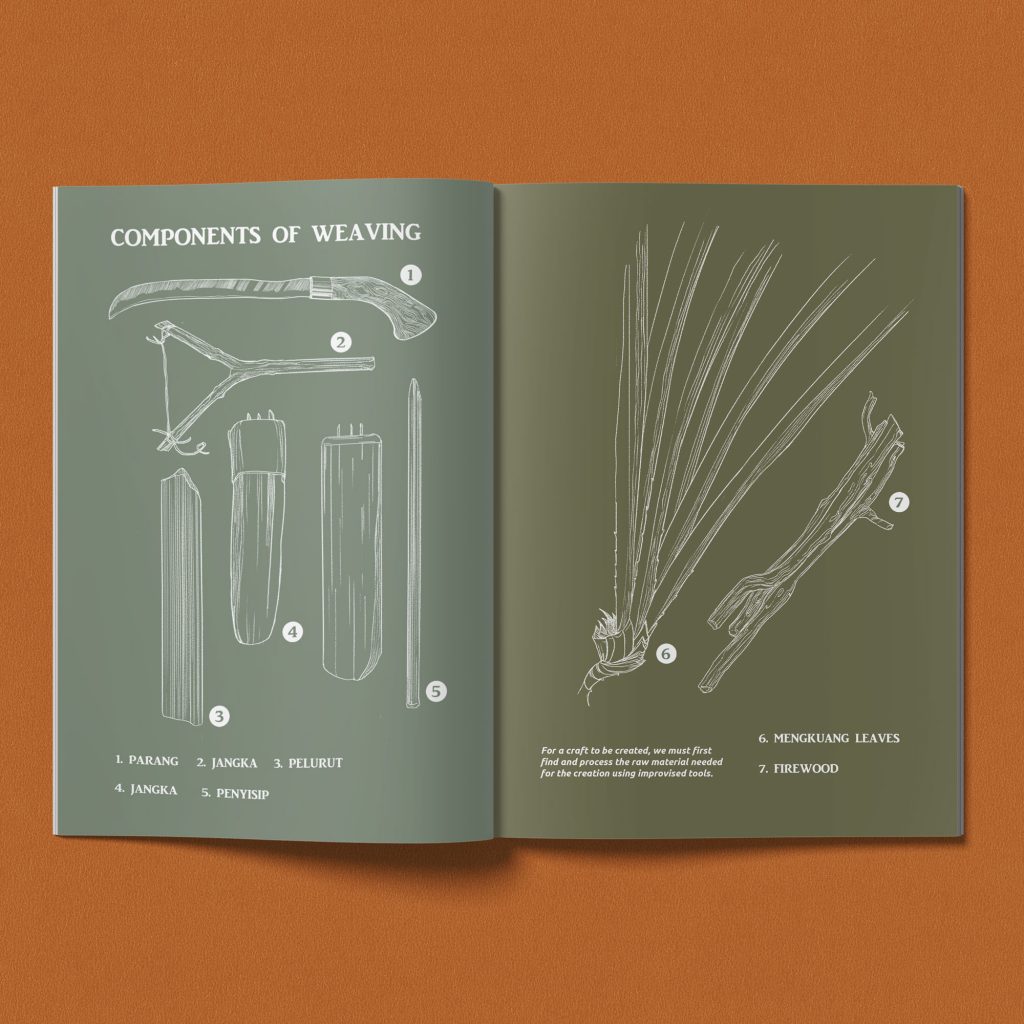

The process of weaving is time-consuming. Before the weavers could even sit down to start weaving, they first have to find the plant (if they don’t plant it in their kebun) and process the raw material using improvised tools.

The picture above shows the tools used to harvest and process mengkuang leaves. Each tool plays a role in the multi-step process below:

You can read more in-depth information in our ‘Mad Weave’ zine, which is narrated by Temuan Master Weaver Yau Niuk (Mak Yau) and her daughter Nadiawati Miah.

If you’re still not convinced after our explanation on the intricacy of the weaving process, another step that is often overlooked is the collection of crafts.

Collecting crafts require careful logistic coordination (some trips take half a day to a whole day, some over a couple of days) and may get treacherous, especially when the weather is unpredictable and a storm unexpectedly announces itself.

While some weavers live close to the city, most of the best crafts are found in the interiors of our rainforest. Either way, both still require some amount of travelling, whether on winding tarred roads that gradually become narrow as we get closer to the village or on logging roads that could impede even the most powerful 4WD when it’s raining.

PART 3: CAN THEY MAKE MORE AND WHEN CAN GET AHHH?

Of course, but please order in advance so you can get the crafts in time for your occasion! Weavers are not factories. They are artists—and like all works of art, creation takes time.

Besides the laborious steps above, there are other factors that can affect the craftmaking process as well.

Harvesting mengkuang, or any plants to be made into weaving fibres, is subject to the weather. The mengkuang cannot be sun dried during wet seasons and harvesting fibres such as rotan, bertam and bamboo can be dangerous if it’s been raining endlessly for days. Trails would turn into mud (what we like to refer to as ‘trek sambal belacan’) and rivers would gush with strong currents.

Meanwhile, some villages don’t have electricity so they can’t weave at night, and the day time is spent foraging, hunting, or preparing the land for the planting season.

The weavers also observe taboos, such as no cutting of mengkuang leaves during the full moon or no weaving when in mourning.

THE COMMUNITIES WE WORK WITH

Kampung Tangkai Cermin, Perak (Semai)

Kampung Kembok & Kampung Pen, Pos Piah, Perak (Temiar)

Kampung Kenderung, Pos Lenjang, Pahang (Semai)

WHY BUYING ORANG ASLI CRAFTS MATTERS

It’s only through your purchase that craft production can continue. When you take a craft or two home, you create the opportunity for the weavers to weave more and thus improve their skills. For example, we’ve witnessed how Mak Cik Remah’s weaving improved over the span of two years and her dedication to learn new weaving techniques such as the notorious mad weave.

Plus, you’re supporting their income generation besides the usual cash crops. With an increase of the larger public’s appreciation for craftmaking and its skills, as well as the draw of income-making, the Orang Asli youth will in turn gain the interest to learn weaving from their elders in order to pick up the skill and earn for themselves through craft sales.

In a way, you’re indirectly promoting the transmission of intangible knowledge, which helps preserve Orang Asli crafts—although continuity of crafts ultimately depends on forest health (for availability of materials) and land security (for utilitarian purposes of crafts).

Above all, you are part of the craft ecosystem and its survival (in terms of keeping forests intact, keeping crafts production alive, and keeping the transmission of skills going).

If we want to safeguard our indigenous culture of crafts, we must safeguard both the people and the forests.

Before we end this article, there is another reason why it matters to buy Orang Asli crafts, which is often overlooked.

It’s because crafts carry stories, in itself and also in its doing.

While weaving together, weavers share and tell stories of the past, of days long gone. It’s also about the transmission of stories that are otherwise untold in history and unwritten in books.

Whenever they weave together, Mak Yau would share stories with her daughter. One story is about the gigantic mad weave basket that was once used to keep their forages, harvest, or household materials. However, they no longer weave a basket of that size when the wild mengkuang became locally-extinct with the peat forests replaced by monoculture plantations. It was a story of the loss of raw materials and the loss of use.

So the next time you wish to buy an Orang Asli craft, remember all the above.

Approach the craft with a different perspective. See it not as a finished product or a charitable good. Understand the story behind the craft, and the beauty of the people, culture, and their ways of life that give rise to the craftsmanship, which are all embedded in these handmade crafts.